Highlights from the Psychotherapy Networker Conference

I just recently returned from the Psychotherapy Networker Symposium that took place March 22-24, in Washington, DC! As you may know, I like to share

It can be so infuriating to have a couple come to you for help, and then they refuse essentially all the help you try to provide!

I’ve been there, and you have too – possibly too many times to count. And in a lot of these situations, we’re seeing a couple whose relationship is filled with passive aggressive behavior.

In a recent post, we took a look at the patterns that keep these couples locked in loops of unresolved conflict. Today we’ll explore specific ways to stay out of the frustrating labyrinth that passive aggression creates.

If passive-aggressive patterns show themselves early, you can be sure that fear and defensiveness are already crouching in the corner, waiting to pounce the moment you pose a direct question that might expose one or both partner’s vulnerabilities.

These patterns began in childhood, when one or both partners discovered they weren’t going to receive the love and support they needed. Passivity became a way of dealing with grief and disappointment. Anger followed as they became enraged about their emotions that went unseen and unsupported by parents, caregivers, or other powerful adults.

Now, you’re witnessing what happens when hurt children grow up not knowing how to articulate what they desire and are not able to take positive steps to move forward. Blaming others becomes a way of coping with the disappointments of life – a deeply flawed solution that spawns its own set of problems.

Not knowing what they want is a form of self-protection to avoid being painfully disappointed in a failed attempt to achieve what is important to them. When you ask a common therapy question about what they want, the responses describe what they don’t want or are vague elusive answers. It is very challenging for the client or therapist to get clarity.

Passive aggressive responses show up among people of many different personality types. These responses often take the form of complaining strongly about a problem or situation without participating in moving things forward.

Yes, a part of this client wants things to be better. But they are too frightened to release their entrenched dysfunctional coping mechanisms.

If you start by tackling this couple’s problems head-on, you’re likely to hit an immediate series of roadblocks. Neither person wants to take the risks or make the sustained effort involved in learning new skills, cultivating compassion, improving listening, or gaining insight into their own behaviors. Instead, they want you to do 100% of the work and change the other partner, because this is where they believe the problems all lie.

Incidentally, when you directly address these “problems,” you trigger a wave of defensiveness and behavior designed to lead you off course.

Here’s one way to approach this dilemma. Have a discussion with the couple about the difficulty EVERY person struggles with in attempting to improve habits, attitudes, and emotions. A part of every person seeks to be relieved of pain, anguish, insecurities, fears and bad habits. But another part of us is highly reluctant to give up self-protective coping strategies we learned earlier in life.

For example, you might say, “Take a moment and each of you reflect on how you would like to be seen by your partner in an important part of your relationship. Reflect on the effect it would have on you to be seen that way. Then reflect on what you would be doing differently to help your partner to see you that way.”

Then discuss what they came up with.

Then say, “If change was easy or simple you would just go out and do it. So let's discuss why it would be hard for a part of you to actually go forth and create this change on a consistent basis.”

This approach sets the stage to do good two-chair work. The “aspiring self” talks to the “protective self” and the therapist guides the discussion between the two conflicting selves.

Tell your couple that whenever we talk about goals here we need to keep in mind those internal battles. It is not enough to say you want your partner to change. We need to understand why it is difficult for your partner to give you what you want.

And it is also important to understand how you can make it easier for your partner to give what you want! When you make it easier for your partner to give you what you want you are working as a team.

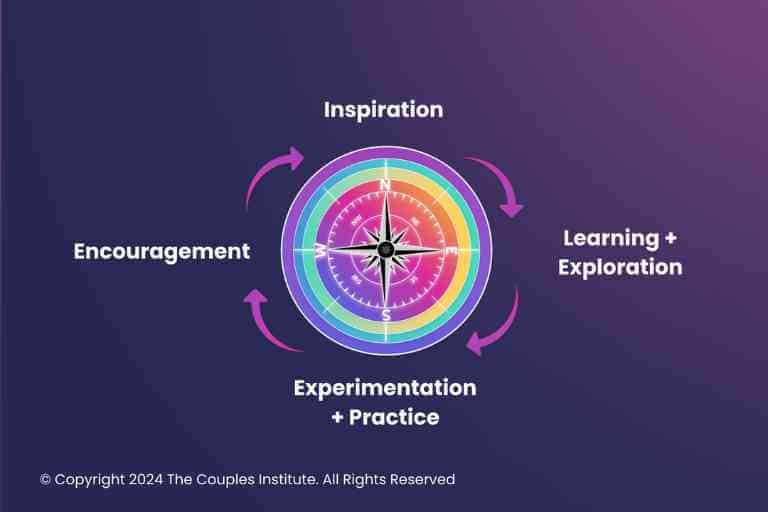

This change in perception dovetails with the Developmental Model, which fosters the agency of each individual in order to improve their relationship.

Taking a leadership stand also relieves you from assuming far more responsibility for this couple’s progress than you reasonably should. It places you in a position of strength, seeking to guide them but not save them.

In a future post, we will explore ways to unearth relationship issues without triggering a passive-aggressive partner’s defenses. I’ll offer you dialogue and exercises that can spark each partner’s curiosity about the other and lay the groundwork for new skills that will nourish their progress.

Before you go, I hope you’ll share a line or two about your experiences in counseling couples who struggle with passive aggression. Are there techniques and concepts that have worked well for you? Tell us what you’ve learned in the comments below.

"*" indicates required fields

We respect your privacy.

We respect your privacy.

"*" indicates required fields

We respect your privacy.

We respect your privacy.

I just recently returned from the Psychotherapy Networker Symposium that took place March 22-24, in Washington, DC! As you may know, I like to share

I’ve specialized in working with couples for 40 years. A “back-of-the-envelope” calculation tells me that’s about 33,000 hours of couples work. You can bet I’ve

Couples often come to therapy with high hopes, vulnerability, and a spoken desire for transformation. They also come with years of pain, hostility, and unresolved

US: +16465588656, 82302466709# or +16469313860, 82302466709#

Webinar ID: 82302466709

We respect your privacy.

We respect your privacy.

Thank you for this and the previous blog. I am new to couple’s counseling and I am trying to learning new and practical strategies for working with couples, especially those that are passive aggressive.

How do you approach a couple where one person gets so triggered by any attempts to know them that they are sent off in to fight or flight or shut down mode? Is that a passive aggressive couple when only one side of the couple has that reaction? And how do you proceed, Can you make them an observer while you deal with the more functional client and their reaction to those kind of responses from their point of view or are there other better approaches? How do you define the couple stage when the two people in it seem to be in almost opposite places?

Excellent example

” how you would like to be seen by your partner in an important part of your relationship.” Can you give me an example?

It’s an intŕesting reading. Every time I see your articles on my page ,I go through it, beginning to end.

Thank you for the invaluable tools I take away from your articles. I am fairly new to couples coaching and here is a tool I used recently, which gave the couple a dramatic turning point (especially for the guy, who was showing loads of passive aggressive responses). This tool comes from the book you recently shared with us – Insight Out by Vann Joines:). using Transactional Analysis (TA ) as a basis for understanding conflict and disconnection in relationship. I have worked with TA for years now as a communication model and am very comfortable with the many concepts it describes.

The exercise is part of rewriting our early ‘life script’ we have from early childhood experiences to get in touch with our own early life messages and help decide what you want to change for yourself: Hope this offers value to the community:)

Close your eyes for a moment and imagine you’re about 6 years old and hearing all the messages you have been getting from your parents. Use the following prompts to describe your experience:

1. Get in touch with what you’re experiencing emotionally as you hear those messages.

What are you feeling?

2. As you’re feeling that way, what are you concluding about your parents and about yourself? You are ________________________________________ and I am ___________________________________________________________________________

3. As a result of what you’re feeling and concluding, what are you going to do to take care of yourself? I’m going to __________________________________________________________

4. What’s your fantasy of what will happen if you do that? That way, ______________________________________________________________________________

5. If things get bad enough, what will you do? If things get bad enough, I will ______________________________________________________________________________

What’s your fantasy of what will happen then? And then